The legend goes like this: Richard La Fort saved William the Conqueror from an arrow with his shield at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Newly crowned King William then endowed lands, a knighthood and a new name on Sir Richard: ‘Fortescue’, meaning ‘strong shield’. How could I – someone with two branches of Fortescue in my ancestry – not visit the site where it all began? A few days R&R to see out 2016 on a high note took us all the way to Hastings on the East Sussex coast.

Bodiam Castle

As someone who loves castles, we weren’t going to miss a visit to Bodiam Castle on the way down. The round corner towers and mid-wall square towers with their crenellations reflected off the wide moat in the afternoon glow of the sun. Long thin archers windows in the high stone walls glared down at us as we walked the perimeter to reach the walkway. Crossing the moat entails walking footbridges where once would have floated boats, passing the ruined barbican and over a tiny octagon-shaped island to the massive wooden doors and original wooden portcullis. Considering the castle was built by Sir Edward Dalyngrigge in 1385, that’s very old wood. Built to stop a French invasion during the Hundred Years War it’s design is nowadays considered to be more ornamental than practical, even described as an ‘old soldier’s dream house’. As such, it really puts on the picture postcard show with photographic vantage points that use up all the space on your camera.

Costumed guides walk you through daily life of both sides of the household – the lordly residents and the lowly servants. The castle boasted an innovative feature for its time with 17 fireplaces in the residents rooms. As the internal walls and floors have been destroyed or ruined they leave the outer walls dotted with the fireplaces to give an impression of the rooms. Of course, there were no fireplaces on the servants side, though their kitchen hearths would have been enough to warm the whole of East Sussex I’d imagine. I guess you need an equivalent-200 burner stove top when cooking for the knight and all his mates after a tough day riding around in chainmail.

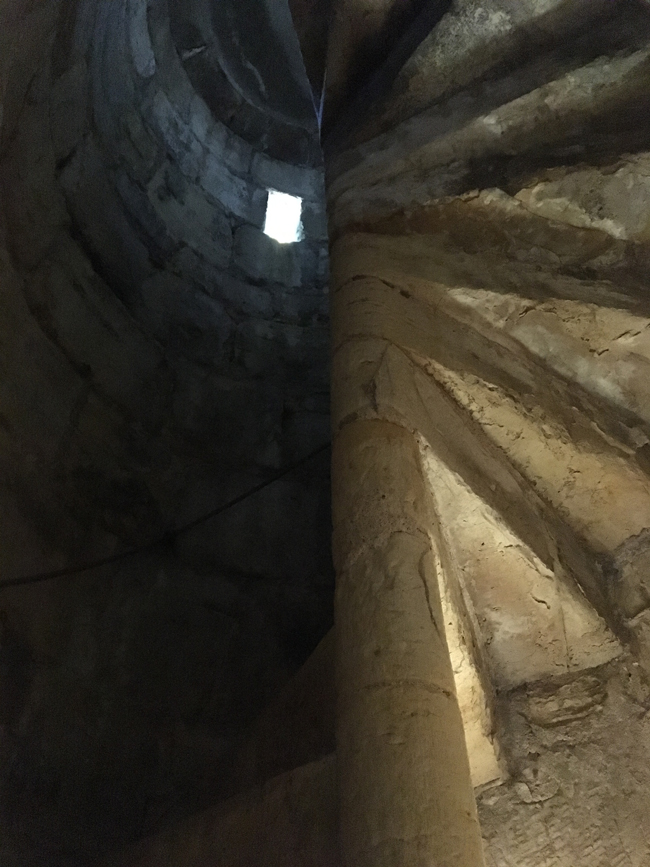

Up and down tight winding spiral staircases we went, stepping out into rooms with bare furnishings to recreate original scenes and views in every direction. Along the battlements and atop the towers the winter air and glorious sunshine rested a stunning calm over the countryside landscape and the romantic idea of history without the reality easily took hold.

Hastings & the East Sussex coast

The fog enveloped us as we headed to the coast and the seaside town of Hastings. While it’s famous for a battle that wasn’t actually fought there, it’s also known for it’s tall black fisherman’s huts – part of the Stade and site of Europe’s largest beach-launched fishing fleet which has been operating for 400, possibly 600 years. The shingle beach had its share of seagulls however the water was not so inviting in mid-winter. Walks through the older parts of town showed up the quintessential seaside resort town with sweets shops, antiques, bunting, the Ye Olde Pumphouse, pubs and fish and chip shops aplenty all claiming to have the best local brew or battered cod. Mini-golf, noisy arcade games and a promenade all completed the stereotypical vision with the only omission being the ice-cream carts who wouldn’t be doing much trade in the cold, blustering wind.

When we travel, one of our favourite things to do is a makeshift picnic in our hotel room for dinner. Dressed in our pyjamas, using the cavity of the window as a fridge and appropriating the tea set tray for a table, we manage to keep the oil from olives and sundried tomatoes off the bed linen and watch something usually travel related on the TV – in this case, a doco by Simon Reeve. It’s our version of roughing it…without the bugs and campfire ash getting in your beer.

Trekking all the way to the East Sussex coast means going out even if the weather isn’t conducive to thoroughly enjoyable sightseeing. Heavy with cloud and threatening rain, we drive along the coast roads, through little towns and tiny villages, barely changed in many years as the momentum of progress hasn’t quite reached all ends of the land. Though part of the fabric of the story behind the Norman conquest of Britain, areas outside of Hastings don’t seemingly advertise their connections. Visiting Pevensey Bay we hoped to see signs proclaiming to be the first patch of soil upon which William strode as he prepared to invade…but alas, nothing to capture on camera. Keeping the peeping tourists at bay seemed more favourable as these towns left it up to Hastings and Battle to cash in on the historical tourism.

Other historically-significant reasons to exist however, for making the pilgraimage to this distant neck of the woods – Beachy Head. During WWII it was the last piece of Britain the 110,000 aircrew of the Royal Air Force Bomber Command saw as they headed out on raids over Germany. 55,573 gave their lives and 11,000 became prisoners of war. For so many, Beachy Head’s gleaming white cliffs were their last sight of England. Ever. On the day we visited we saw nothing of the white cliffs as the fog and cloud wrapped us up so completely we could barely see a few metres in front and kept our car speed down low on the narrow rural roads.

Battle

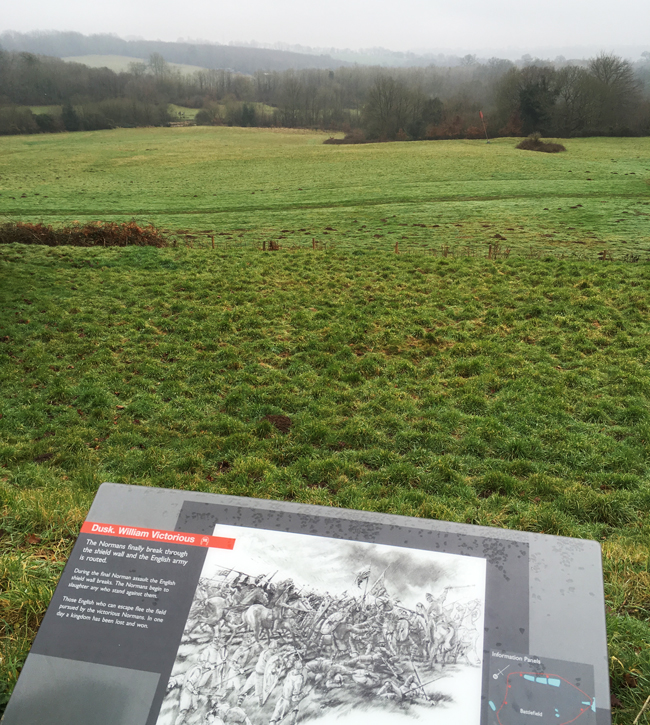

Heading away from the edge of Britain we arrived in Battle with fingers crossed the 1066 site was open during the Christmas period. In this case, crossed fingers worked and they weren’t unbusy either which was surprising. Taking our cues from the helpful audio guide we navigated ourselves around what turns out to be a much-smaller-than-expected field where the focus of the battle took place. For all the lore and history and famous tapestry created, it’s a tiny stretch of sloping land with a few trees, and these days plenty of wood carved full-scale sculptures of warriors to guide you around. I was so surprised to see how only a small area could change the course of a country’s history. As the town didn’t exist in 1066 the whole area would likely have been used – infantry camps, space for cavalry horses etc, however the ridge and ground that is preserved is regarded as the area that witnessed the climactic events of the battle.

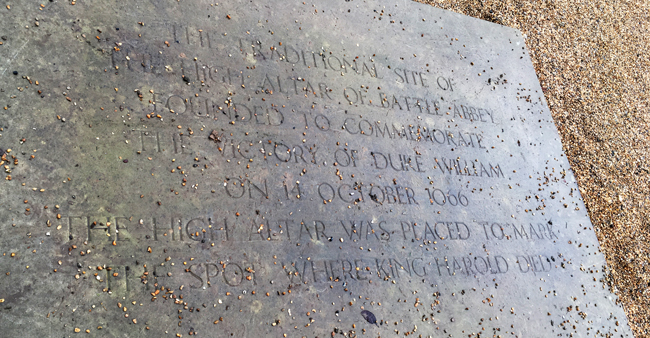

Battle is so named for the Battle of Hastings. Battle Abbey was founded by William to commemorate the battle and dedicated in 1095. The high altar was located on the site where it’s claimed King Harold died. The Abbey gateway is still alive today, housing the gift shop and ticket office, while the other surviving building was leased to Battle Abbey School after WWI and is used as such today. Other ruins give you a glimpse of the life of the monks with the common room and upstairs dormitory mostly intact. The Abbey sits on the top of the hill defended – eventually unsuccessfully – by the English and gives views over the battleground which hosted the Norman conquest. Even with the audio guide it’s a little difficult to imagine relatively small numbers of infantry, cavalry and archers fighting from 9am till dusk to settle the score in favour of William. Modern estimates put the Normans at 7,000 to 12,000 men and the Anglo-Saxons at between 5,000-13,000 men. William was fighting with less men, uphill, in early winter and still managed to win. Must have been due to the help of my great-great-great-great…..-great grandfather Richard!