Much has been documented, displayed and condemned about the atrocities of WWI. The landscape now shows barely a scratch of its history until you encounter a cemetery or memorial, or a farmer reaps a lead harvest. Remnants consist of metal objects – guns, tanks, helmets and crops now cover the low ridges running across the gently rolling land, once ripe with the stench of mud, blood and decay.

The battlefields tour for this year focused on Ypres and the Western Front, to mark the 100 years anniversary of the 3rd battle of Ypres, more commonly known simply as Passchendaele. As was the case last year, the three days are a roller coaster of emotions, education, stark realisations and disbelief made in the middle of battlegrounds and gratitude to the many, many fallen. There are many famous battles, victories and heavy losses, poignant memorials and legends of bravery and sacrifice. Too many.

Our first stop was the Dunkirk Cemetery and Memorial, a timely stop as the Christopher Nolan film had just been released. A reflective garden, several rows of crosses and countless names on large monoliths line the walkway to the remembrance dome. Frosted glass panels create the walls of the dome shelter and depict the struggles of the evacuating soldiers. As with so many of the cemeteries dotting the landscape, the surroundings next door are normal houses, shops, fields and signs that life picked up the pieces and carried on once the guns fell silent. A sign of so much loss of life, surrounded by the living just going about their business.

There are also the other, less famous yet still unbelievable chapters of The Great War that refresh your feelings of desolation at the sheer brutality of human beings. The Wormhoudt Barn Massacre site is one such memorial, making sure history is not forgotten. Here, nearly 100 British and French POWs were crammed into a cow shed before grenades were thrown in by their Waffen-SS captors. The grenades didn’t kill everyone, largely due to the bravery of two soldiers who threw themselves onto them, so the SS soldiers ordered two groups of five to come out, who were then shot. The SS soldiers then fired countless rounds into the barn hoping to finish the job. Eighty men were killed and several died of their wounds in the next few days while the precious few who did escape were found by the German army, treated for their wounds and sent to POW camps. Justice was not served and those believed responsible not brought to trial. Some wounds just never heal, least of all those suffered from heinous war crimes.

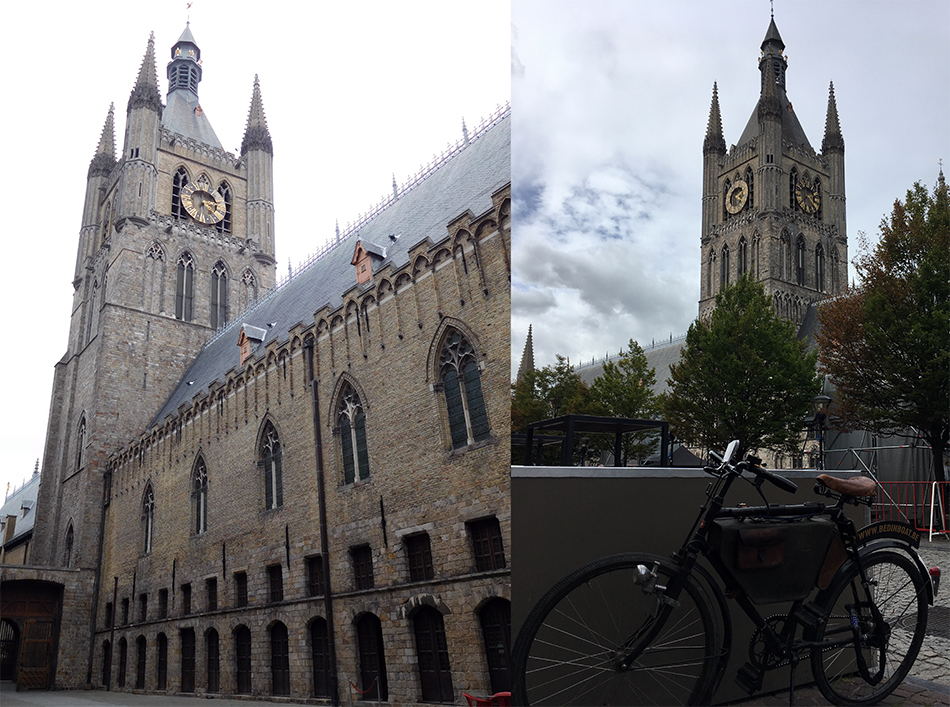

Ypres town is magnificent. The large central square bordered by monumental churches and historic buildings including the 13th century Cloth Hall which was rebuilt from bomb-shattered remains to its former medieval glory after the war. Chocolate shops, waffle houses, bistros and wine bars line the beautiful square and with good weather, it is a lovely place to watch the world go by. The view from the Belfry is amazing if you’re keen to make your way to the breezy and cramped top.

Housed in the Cloth Hall is the comprehensive In Flanders Fields Museum.

During our visit, preparations were in full swing for a BBC commemoration to mark the 100 years since the battle at Passchendaele with large stages, stadium seating, towering boom lights and cameras, cables running for miles and dress rehearsals delighting us while we enjoyed dinner nearby. It looked like it was going to be quite the show with projections on the Cloth Hall belfry of a rising flurry of red poppies, it brought a lump to the throat and even in rehearsal, mesmerised the accidental audience.

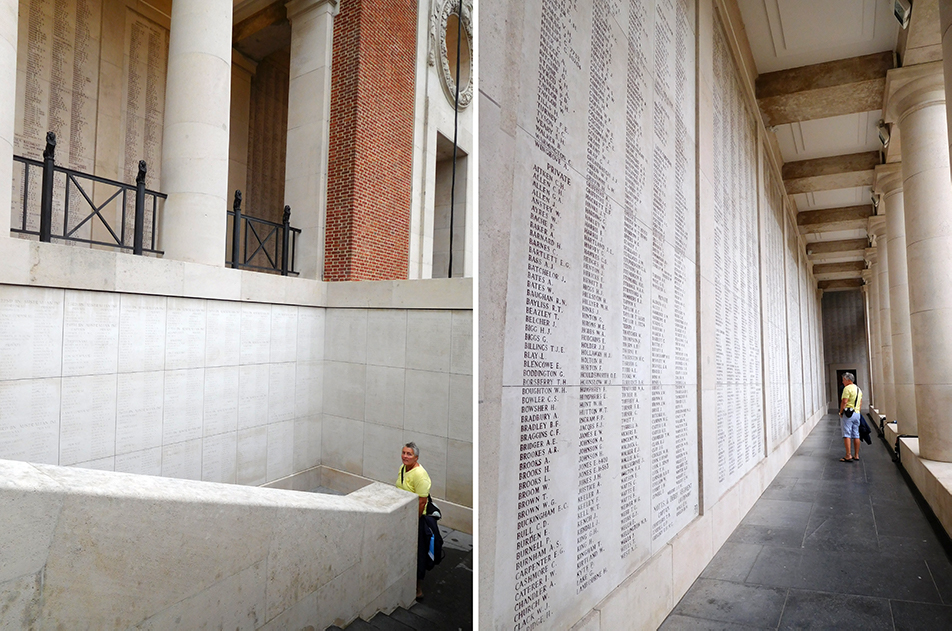

The Menin Gate will now always have a firm spot in my memory. The enormous archway with bright dome and thick walls is almost completely covered in the names of the missing. Venture through the side arches on either side and you are confronted with stairways to the upper sides of the gate, with every surface carved with names. So many Australians are named here, sons, fathers and brothers of a country that at the time was just starting to make its mark in the ‘Western’ world, still clutching to the apron strings of Mother England and learning the hard way it was time to stand on our own two feet. As we walked up the stairs we reached the outside walls and upper balcony of the immense gate, the names continued. We attended the Last Post Ceremony both nights of our stay in Ypres. At 8pm each night, buglers from the fire station assembled under the outer end of the archway to play the most haunting of tunes. A minute’s silence, the Ode and then Reveille rang out of the echoing chamber, the gathered crowd reflected with teary downcast eyes and held loved ones close. Wreaths were laid by politicians, family descendants, veterans groups and our very own CSSC while the Red Deer Royals marching band from Alberta, Canada performed on the first night, a Welsh choir on the second. It is a stirring and incredibly moving commemoration that each day continues to remember the unbelievable scale of human sacrifice.

Ypres contains several cemeteries and memorials including the Ypres Reservoir Cemetery hosting nearly 2700 burials brought in from smaller cemeteries dug during the war. Ypres Town Cemetery Extension holds 788 soldiers from both world wars as well as graves of permanent staff and family members living and working in Ypres for the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, with their headstones set apart and of a slightly different design. The latter is reached by a footpath between houses and hedges, again a site of the fallen resting right next door to the living.

Near the town of Zonnebeke lies the largest and most visited CWGC cemetery in the world, Tyne Cot. It is the final resting place of nearly 12,000 Commonwealth and four German soldiers, overlooked by the names of 35,000 soldiers with no known grave. Over 8,300 of the graves are unnamed. Again, preparations for the commemorations were well under way with seating for some 4,000 descendants of soldiers there buried. Even though we knew the numbers and facts, the cemetery itself didn’t overwhelm me like I thought it would. Its geography serves to almost hide the enormous number of headstones, with the slope away from the walls of the missing gradually revealing itself from behind some tall trees. It is hard to see the whole area from one spot, you need a drone to take it all in at once. Two German pillboxes sit ragged and dull amongst the headstones, blooming peachy-orange roses crowd around the gleaming white blocks, growing well from the tender care of the gardeners.

Bedford House Cemetery is truly beautiful, if you can call a cemetery ‘beautiful’. Rather than the standard square lawn it seems to wind between fields, over a deep sided former moat and abounds in bright flowers and flourishing gardens. Domed shelters offer somewhere to rest and reflect, lines of graves run in all directions encouraging visitors to spend time meandering and viewing each plot, to pass through small gates to separated enclosures. Before the war there stood Chateau Rosendal, with gardens and a moat, while during the war is was a field hospital and brigade station. It had grown into five cemeteries at the time of Armistice. Over 5,100 Commonwealth servicemen are buried or commemorated in the cemetery, more than 3,000 of which are unidentified. One of the headstones which did catch our eye was of a soldier from the Glosters – Uncle Charlie’s old stomping ground – with the surname ‘Phillips’. While he was no relation, it still makes you pause for thought. We left a note of thanks and shed a tear before moving on. It’s hard to describe how the emotions sneak up on you. We join these trips with a main aim to learn more about the war and pay our humble respects. We know we’re going to find things difficult to understand, to fathom the brutality or sometimes to relate to the life of the times. It can feel so foreign to see rows of crops over the same ground where a wartime photo shows barbed wire and bomb craters full of sticky, thick mud. It can also make me put a guard up – to steel myself for the description of misery to come from our very knowledgeable guide. So when a familiar name stands out among the too many others, when the emblem carved on the headstone is from home or when the peaceful atmosphere shrouds you and your thoughts with whispers of the trees, it’s impossible not to be incredibly moved.

A comment from one of our group was how so many could be unidentified. Some reasons are burials being moved from original or front-line graves to official cemeteries after the war or the utter destruction due to shell-fire injuries making it impossible to identify the body. That they were found at all could be considered a triumph. So very many were literally swallowed up by the oozing mud. Soldiers talked of sinking knee-deep with each step, the low-lying ground made perfect conditions for sticky, clay mud and the bombs and shell continually tore up the ground, turning it over like kneading bread dough, gathering everything and rolling it deeper and deeper, never to be seen again.

The battles on Messines Ridge involved several tunnels dug under the trenches, loaded with mines and timed to take the enemy by surprise and announce the start of offensives. Massive craters still remain, serving as war graves for the many men caught in the trenches above the explosions. The Spanbroekmolen Mine Crater Memorial – Pool of Peace, now seems a large tranquil pond, shaded by trees and covered in water lilies. Looting isn’t an old crime, with some still fishing out German helmets with magnets on the end of the line instead of bait. The pool is the resting place for around 500 German soldiers caught in the blast. From the roadside of the crater entrance you can see clear across Messines Ridge and point out landmarks of the Western Front.

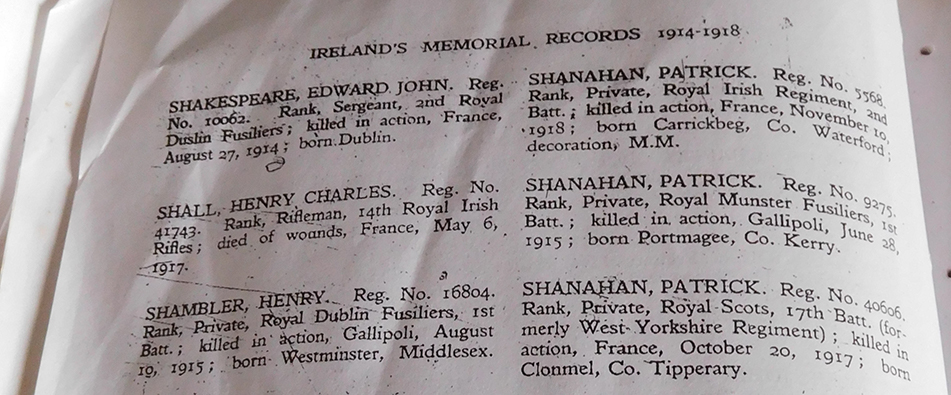

The 34m tall, dark grey stone tower of the Island of Ireland Peace Park is a traditional Irish round tower and is partially built with stone from Tipperary and Mullingar, County Westmeath. The design means the sun lights the interior only at 11am on the 11th of November. The park serves to commemorate the sacrifices of all those from the island of Ireland. Large dark stone blocks line the entry walkway with passages from poems and letters of Irish servicemen.

“So the curtain fell, over that tortured country of unmarked graves and unburied fragments of men: Murder and massacre: The innocent slaughtered for the guilty: The poor man for the sake of the greed of the already rich: The man of no authority made the victim of the man who had gathered importance and wished to keep it.” David Starret, 9th Royal Irish Rifles

The conception and construction of the Peace Park was not without its political hurdles, with plenty of different opinions on who should be involved, who should pay for and maintain it. Still it is a symbolically united Ireland, forever remembering her men sacrificed on Flanders fields.

Messines Ridge features heavily in New Zealand’s military history, their ANZAC spirit coming to the fore time and again. The Messines Ridge New Zealand War Memorial was erected to honour the men of the New Zealand Division who on 7th June 1917 captured the ridge and advanced 2000 yards through Messines to their objective on the eastern side. The memorial holds two original German bunkers unmoved from their position in the Uhlan Trench.

The Cross of Sacrifice stands tall over the circular stone memorial of the Messines Ridge (New Zealand) Memorial to the Missing and Messines Ridge British Cemetery. The names of more than 800 NZ servicemen with no known grave who died during battles on the Messines Ridge during WWI are etched on the rounded blocks. Further up the footpath is the lawn of headstones of the Messines Ridge British Cemetery commemorating more than 1,500 Commonwealth servicemen.

The Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing stands within the Berks Cemetery Extension where both are guarded by huge stone lions and several nation’s flags. The cavernous memorial’s walls are inscribed with the names of more than 11,000 Commonwealth servicemen with no known grave who were lost during the battles fought outside the Ypres salient, including Fromelles and Loos. Three recipients of the Victoria Cross also appear on the walls.

Across the road lies small Hyde Park Corner (Royal Berks) Cemetery, including the grave of Albert French, a 16-year-old soldier from Wolverton, Buckinghamshire – not at all far from where I now live and work. Also at rest here is Jewish German solider Lt Maximilian Seller who was killed in 1915 as he led an assault against a British trench near Ypres. A British sergeant, Victor Rathbone, who was also Jewish, ordered that he be buried with a Jewish burial service. I can’t help but wonder what a difference 20 years and a new war makes.

The unassuming Poperinghe New Military Cemetery is a peaceful area nowadays, however during the war it was a casualty clearing station and field ambulance station. It is now home to over 670 fallen Commonwealth servicemen and more than 270 French soldiers. Among the graves are Belgian nurses who died alongside their charges. Members of the British Civil Service Rifles are also buried here which was of greater significance for our guide, being as our group was made up of members of the Civil Service Sports Council.

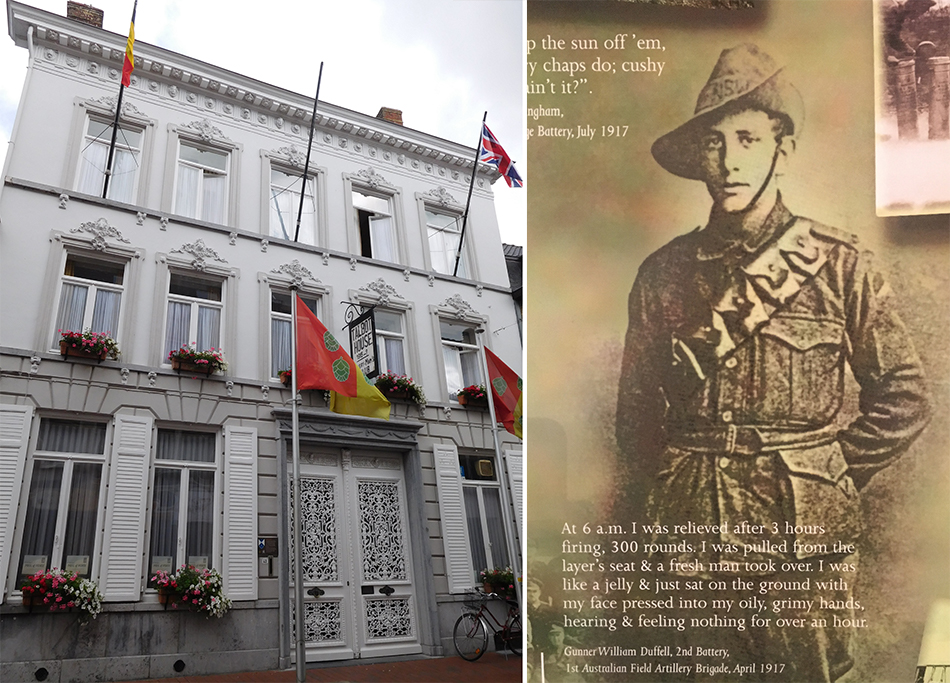

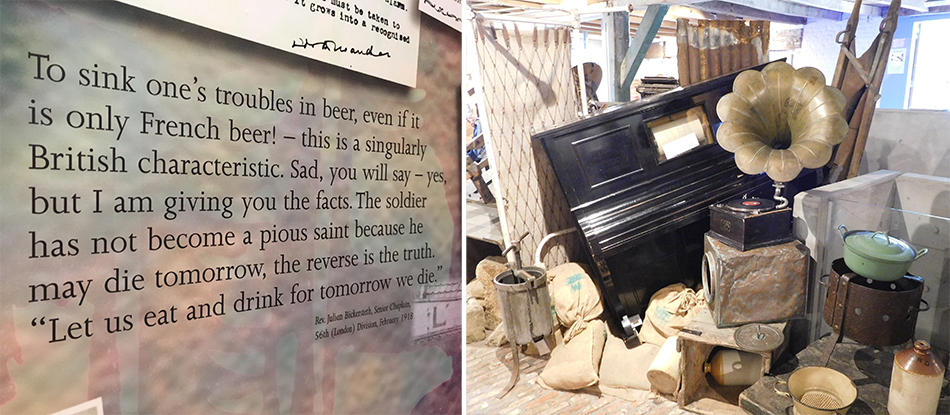

In the gorgeous town of Poperinge itself is the haven of servicemen on leave – Talbot House. During the war, Poperinge was part of unoccupied Belgium and an important centre for the British away from the front line of the Ypres salient. Talbot House was opened as a welcoming place of peaceful recreation and rest where troops could enjoy films, civilian company, a real meal and warm shower. Today’s museum preserves the office of the founding army chaplains Neville Talbot and Philip “Tubby” Clayton. The Every Man’s club was open to anyone, regardless of rank and offered an immense boost to morale as well as sing-alongs. These days you can still play the piano, enjoy a cuppa in the tea room, or even spend the night in the guest rooms. It’s still an Every Man’s club.

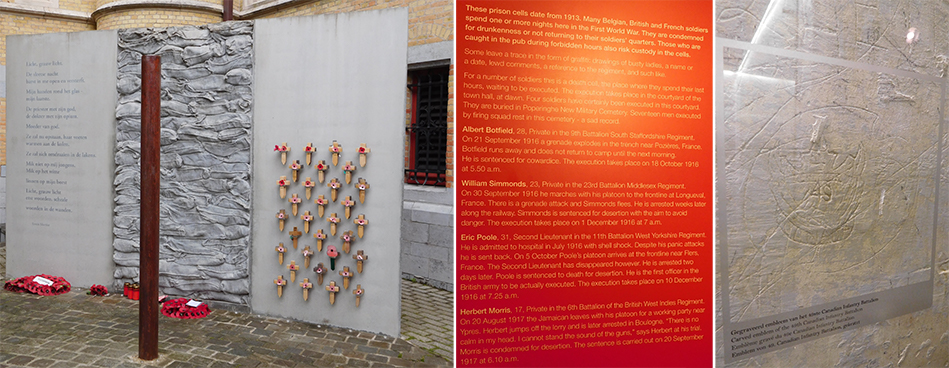

On the flip-side of the frivolity of Talbot House is the Shot at Dawn Memorial. Behind a side door, shrouded by the back walls of town buildings, in dark small cells, soldiers found guilty during court martial for desertion or cowardice waited to be shot at dawn. Modern research concludes several men executed were suffering shell shock and unable to function such as the army demanded. Some were made an example, to warn others of their obligation to the armed forces. On reflection, over 100 years later almost all have been pardoned…a little late don’t you think? In the only way it could be worse was being summoned to be on the firing squad as it was generally men from the same unit who had also fallen foul of military law. Over 300 men were executed but only one has this fact marked on his headstone. The cells and the execution pole remain to remind visitors of the injustices of war, even from your own side.

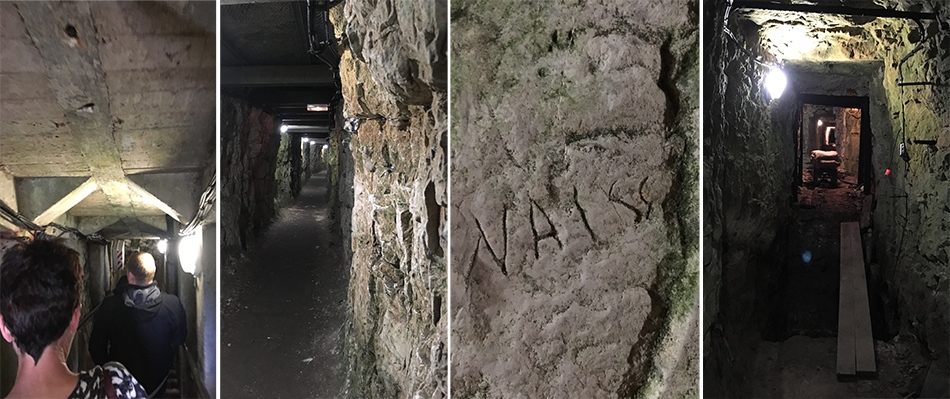

Vimy Ridge is a major part of Canada’s war history and part of the larger Battle of Arras, fought in France during WWI. A 250 acre swathe of former battlefield is now overseen by enthusiastic, youthful interns of the Canada Parks Agency who take you through the remaining tunnel and around the trenches. The sandbags have been preserved in place under a thin layer of concrete, you can even see the seams and crosshatch of the original hessian sacks. If only sandbags could talk, I’m not sure I could bear to hear their stories. Bomb craters and bunkers dot the trench lines and rusting machinery is still visible. Most of the land is off-limits, like so much of the Western Front and battlefields, due to buried mines still lying in wait. The undulating ground rises and falls in perfectly rounded mounds and craters, now carpeted with thick beds of pine needles. The breeze rustling the trees provides a symphony of solace, the gentle swaying of branches enough to hypnotise a hardened war historian.

Right: View from the sniper pods that punctuated the front line.

The chalky ground of Vimy Ridge led to a substantial amount of underground warfare, with numerous tunnels dug 10m deep and running perpendicular to the trenches. These provided communication and supply lines, a quick way to advance troops from reserve lines to the front and water reservoirs and hospital stations, light rail lines, command posts, machine gun and mortar posts. A section of the 800m long Grange Subway is open for tours nowadays so we ventured down into the pitch darkness, eyes unable to pick out a single thread of light. The porous chalk walls are occasionally carved with graffiti, moss grows near the soft glow of installed lights, fed by the natural seams of moisture trickling through. Our guide recounted the night before battle commenced, when soldiers readied for action crept into the tunnel fully loaded to wait in absolute silence for the order to advance. As if sitting in the dark, with no talking, eating, moving allowed for several hours to ensure the Germans didn’t hear or suspect wasn’t enough, the charge was put back by a day, however the soldiers were kept in the tunnel, again to fool the Germans. No thanks. The Canadian Expeditionary Force did successfully capture the ridge, their advance beginning under creeping Allied artillery fire, the units leapfrogging with reinforcements to push the Germans back. Between tunnels and mines, trenches and heavy howitzers, it’s a wonder anyone survived at all. Some 3,600 men were killed and more than 7,000 wounded.

Today a flock of about 400 sheep graze the woods and parkland, their gentle grazing not disturbing the mines while keeping the grass low. We wended our way through the preserved trenches, huddling into the sniper and lookout bunkers, trying to imagine the feeling of knowing your enemy was literally a stone’s throw away.

The twin columns and mammoth sculptures of the Vimy Ridge Memorial tower over the highest point of the ridge, on top of Hill 145, their commanding view sweeps vastly over the Douai Plain, about ten kilometres from Arras. The land was granted to Canada by the grateful French. Taking eleven years to build, the monument features the names of 11,285 Canadians who lost their lives in WWI in France but have no known grave. The names cover the huge base of the memorial and yet they are only some of the more than 66,000 Canadian men who gave their lives in the Great War.

In all the sites we visit, we see so very many graves with the simple inscription ‘A Soldier of the Great War’. Unable to be identified by name, sometimes they may be lucky to have their unit, role or nation included. Several headstones stand butted side by side, indicated one grave holding more than one man, their bodies so shattered by shellfire they are unable to be prised apart and so slumber for eternity, entwined. And then we come to memorials such as Tyne Cot and Menin Gate and Vimy Ridge and Thiepval and see name after name after name carved into stone, the only remnant they were there, no other marker possible, their body interred where they fell by the relentless continuing of the battle around them. It’s the sheer number of names that gets me. It’s hard to fathom the statistics, the legions of troops sent to their end, in the days of slaughtering war, before today’s technologies existed to send in machines before men.

And while each of these battlefield trips are cloaked in sadness, in a deeply reflective mood imbued with gratitude and respect for the fallen, there is a lighter side. Our fellow tourists and we are connected in our desire to educate ourselves, to honour the dead and remind ourselves how lucky we are to be able to visit such places of beauty without the mud, blood, decay and threat of fascism in wartime. While the wrongs of the world still exist, wars still erupt and power still corrupts, we continue to forget the lessons of the past. With active participation in remembering the fallen and respecting the values of their ultimate victory, we still have an obligation and a chance to promote peace. It is now our turn to take up the cause and give peace a chance.

“Sunshine passes, shadows fall; Love and remembrance outlast all.”