I can’t claim to have made a conscious decision to visit war sites and cemeteries after my first fluke of planning, managing to visit Gallipoli on ANZAC Day, however since then I have been lucky. I say “lucky” because I have been able to visit such sites and memorials during the peacetime we enjoy since the battles were fought. And so it is again by a slight fluke that I am starting this post on day 2 of a coach trip to WWI battlefields of Verdun and the Somme, making for a very different kind of long weekend. Our time on the road started well before the French chapter with a few hours down to Folkestone overnight, not a lot of sleep at the Park Inn hotel, early call to meet the coach and my first trip on the Channel Tunnel – while it’s not a very exciting voyage in itself, I find it amazing you can sit on a coach that gets on a train in England and then drives off onto a French motorway about half an hour later. Gotta love Europe and not living in the turbulent times of the Spanish Armada.

Of course it was then a few hours further to get to the Verdun area which is in the Lorraine region.

Verdun is a historic and sentimental place of importance for the French people, and so was chosen by the Germans as the best place to pick a fight and draw French troops away from the Western Front to make headway. The battle of Verdun was the longest single battle of the war and was the primary reason the British launched the battle of the Somme, in order to relieve pressure on the French. Running from 21 February to 16 December 1916 and code-named by the Germans as “the Judgement”, it was designed to ” bleed the French white” – relying on the French to fight to the last man to protect their nationally beloved Verdun. Indeed it seems it might have almost achieved this objective as 259 of the 330 Infantry Regiments of the French Army fought at Verdun at some stage of the battle. Casualties numbered around 360,000 on the French side and 340,000 for the Germans by the time the battle finished, ironically after the Battle of the Somme is supposed to have ended.

Our first stop was a memorial along the Sacred Road – Voie Sacree – the one and only road that brought troops, supplies, everything into Verdun – at it’s busiest it saw a vehicle every 14 seconds and had gangs of mechanics and road builders ready to keep trucks moving and fill in the potholes 24 hours a day. The modern road is marked with bollards to denote the path of the Sacred Road today – if only enterprising thieves would stop stealing the original metal helmets off the tops, they wouldn’t have to replace them with plaster casts.

The Verdun “Glorieux” cemetery is reached by a walk along a gravel road past a scrap metal yard with barking dog and the calming sound of a grinder. The hill is covered in the neat rows of concrete crosses with metal name plates of the fallen. Around 12 years ago a visitor noticed some non-French sounding names and upon contacting the War Graves Commission, established they were British troops who had been listed as AWOL and missing. They now have British headstones and their names updated in the history books.

Now stops at motorway services aren’t usually anything to write about, but I must tell you, it was quite surprising to see a French family who had decided to bring their pet rabbit along on their holidays in a cat carrier. He looked huge, fluffy and very happy in his burrow of straw. A rabbit on a road trip. Well played, Thumper.

Next door to the civilian cemetery in Verdun is the Faubourg-Pavé national cemetery, featuring even more concrete crosses and metal name plates, lined up in rows before a large tall monument. If you follow the path to the back of the cemetery you find an unusual memorial – a carved relief of a man, hung up in rope and a statement underneath dedicating the piece to “Aux victimes de la barbarie nazie. Aux supplices et fusilles, connus et inconnus. 1914-1918 & 1939-1945”. “To the victims of Nazi barbarism, torture and murder, known and unknown.” This victim overlooks 6 cannons – 3 French and 3 German – painted a light naval grey except the wooden wheels and all pointing out in a circle away from each other. Nothing like the weapons of death resting next to their victims, hmm…

Day 2 started with sites inside the Verdun Red Zone, including the remains of the destroyed village of Fleury-devant-Douaumont, one of 8 villages that were completely destroyed and not rebuilt following the war. Such was the utter destruction, too dangerous a task to clear the area of unexploded ordnance and the overwhelmingly toxic land resulting from chemical warfare from the Germans (in contradiction of the Geneva convention to not use chemicals in cannons), that the villages are left as places of reflection. The church is the only building to have been restored in each village. Lining the paths cleared along former roads sit stone blocks with plaques denoting what once stood there, baker, blacksmith, stores and houses. The ground is like the walls of a sound proof room – bomb craters have left the earth undulated, sinking deep and lifting high in round rolling hills. Fragments of bone, rifles, masonry, signs of previous life and death can be found if you break the law and leave the path, risking detonating a dormant shrapnel or gas bomb. The atmosphere was impeccably quiet, save for whispering visitors, the eerie quiet hardly even broken by singing birds. It is as if everything stopped when the bombs finally did.

We moved onto a site of French army legend – the Bayonet Trench. The story goes a group of soldiers were killed and buried under collapsed trenches as they were bombed and they were found after the war by their bayonets poking up out of the ground as they died standing to attention. A US billionaire was so moved by the story he funded the current memorial, a hulking concrete monstrosity sheltering the trench grave and crosses for the troops. It could have happened like that or they could have been buried in a mass grave and the padre returned and placed the rifles and bayonets to ensure his company was especially remembered. Who knows.

The massive L’Ossuaire de Douaumont is a focal point for services of remembrance with its grand ossuary, chapel, bell tower with viewing windows, manicured lawns holding 16,000 crosses, Muslim and Jewish memorials, theatre with a 20min movie about the Verdun battle called “Men of Mud” and souvenir shop. The long halls are covered in the names of soldiers and the floors are beautiful mosaics, the orange glass in the windows casting everything in a warm glow. Below the building are chambers filled with the bones of approximately 130,000 men, all nationalities, piled together, the occasional skull with the gaping eye sockets glaring out the viewing windows at us, mute in death and yet appearing to be screaming. The movie was quite moving, snippets of film documenting the horrible conditions, the movements on the Sacred Road, visions of dying horses, corpses left in peaceful eternal sleep on the tops of trenches as the battles raged on and the wrapping of the ghastly, acid burned barely-there remains of a soldier in a burial blanket, his skin falling off the bones of his legs as he is rolled over, the attendant scooping bits of flesh into the blanket as the poor soul is rolled and wrapped. It’s a vision I’m now unable to forget.

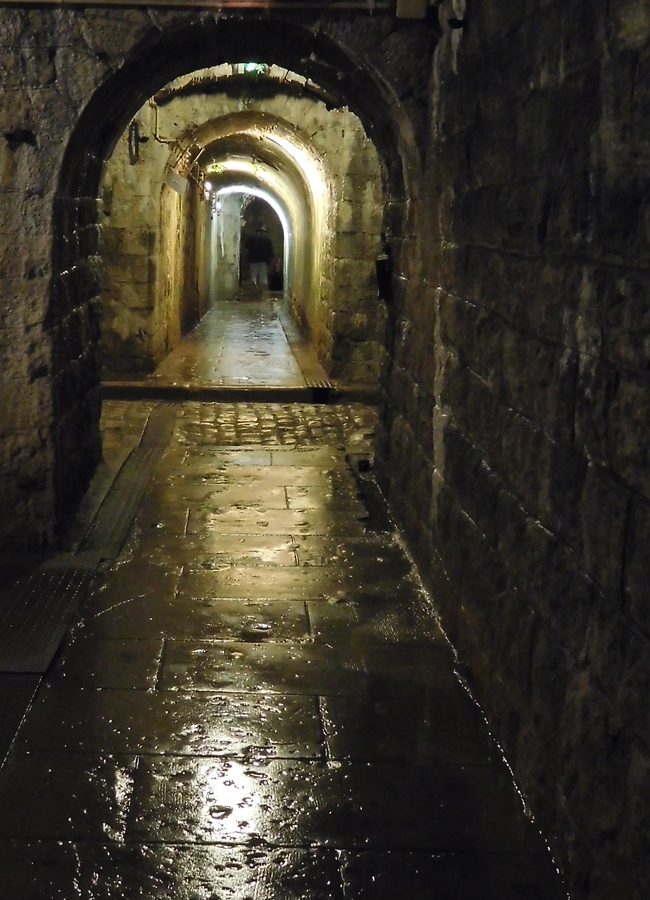

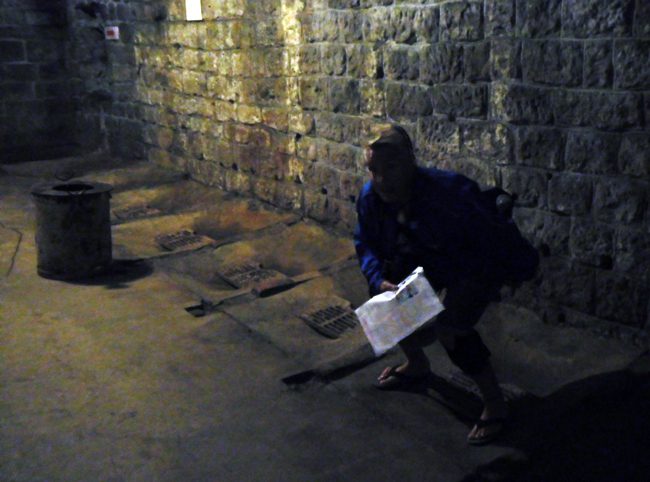

Part of the original defenses for the Verdun area was Fort Douaumont, the last fortress to fall during the Franco-Prussian war in the late 1800’s and another historically significant location for the French. During WWI is changed hands a few times, the first time the Germans took it they were very surprised to only find 56 elderly defenders. Now in part ruin, part maintained, the outside belies what exists under the grass and barbed wire covered top. We took a paper guideline and followed it around to find rooms that once served as barracks, bakery, kitchen, lavatory and latrines, hospital, commanders rooms and messes and the immense Galopin turret 115mm cannon. The counterweights and mechanism to raise and fire it are enormous and now such a relic of a bygone era in war technology. The calcite on the walls mixes with moss and water drops manage to find someone to land on occasionally as they fall from the points of stalactites growing down from the stone archways and ceilings. The damp cold that quickly grabbed our bones made us shiver to think how horrendous the lives of the soldiers must have been, defying death as long as possible in such conditions.

To learn more about the offensive that was meant to relieve the pressure on Verdun – and which became known as the Battle of the Somme took us on a few hours drive past rolling fields dotted with cemeteries. Once you know what you’re seeing, it becomes alarmingly easy to spot the squares popping up in the middle of crops, fenced by stone and a few large trees shading the too numerous head stones. I was reminded of walking the roads around Gallipoli, on a much wider scale.

The Sheffield Memorial Park marks the British Front Line on 1 July 1916 and the shallow trenches that remain were about as far as many of the Pals advanced, such were the losses. The sheltering woods which took artillery shellfire enough to shatter all the trees to bare stumps have regrown and the gentle breeze makes the area very peaceful as it rustles the tall trees.

On 1st July this year, three former Royal Marines arrived at the same spot, taking on the challenge of The Somme Yomp, and walking 650 miles through the UK and France. The team had collected 19,240 remembrance crosses, one for each British soldier killed on 1st July 1916. Each was planted in ground outside the gate of the Pals Memorial to mark the 100 year anniversary and a single poppy has grown and bloomed among them.

Nearby Luke Copse British Cemetery is a small, perfectly manicured lawn, bordered by several headstones with the increasingly familiar inscription “A Soldier of the Great War 1914-1918”. So, so many were unknown. Julie laid a cardboard poppy with a message next to a young man with the surname “Phillips” and we took a moment to reflect in the gently falling rain.

Besides the cemeteries dotted around his land, the resident farmer has another, more alarming, reminder of the war. Over the years, with each plough of the soil, the Iron Harvest invariably bears its dangerous fruit. As farm machinery can dig deeper, more and more shells and unexploded ordinance are being brought to the surface. The land clearing will never be finished. The farmers either put a boulder next to the objects for the bomb disposal squads to come and remove them safely, or as we saw, move the shells to a pile along the roadside.

The Serre Road gives its name to three of the 12 cemeteries I could count along the old battle lines within a 1km radius of the Sheffield Memorial Park, we stopped briefly at Serre Road Cemetery No. 1 which included graves of AIF casualties among its many headstones.

A distinct change of atmosphere descended over our group when we arrived at the Fricourt WW1 German Military Cemetery, the final memorial to 17,027 German soldiers, including the Red Baron…at least for a little while. Just over 5,000 are named and marked with black iron crosses and the remains of the others rest in mass burials with the names of just over half forming a long, continuous lines of letters to cover metal slabs. The rest of them, some 6,477 are unknown. Construction was suspended in 1939 and was only resumed some 30 years later. It’s cold and stark. The hard, black metal of the crosses offers no sentiment, no comfort. Simple, functional, humourless. And no poppies, flowers or tokens of remembrance to be found.

This is near the Pozieres area – a name that chirped in the recesses of my school history class mind. A short drive from Fricourt is the Dantzig Alley British Cemetery in Mametz. It commands a really lovely view over the fields from its position where it holds 2,053 casualties, of course not all are known.

We overnighted in an Ibis hotel outside Albert which served up rustic bread and a generous chunk of local sausage for a free starter – which was a delight – and all mine, washed down with a very pleasing local white wine.

Less than 50 metres up the road from the hotel the next morning we stopped at the Baupaume Post Military Cemetery. It is small by comparison to the many others, containing 229 identified casualties, however is notable for one in particular. Though still to be formally recognised, the youngest Canadian soldier to fight lies buried here – it is possible he was just 13 years of age when he died.

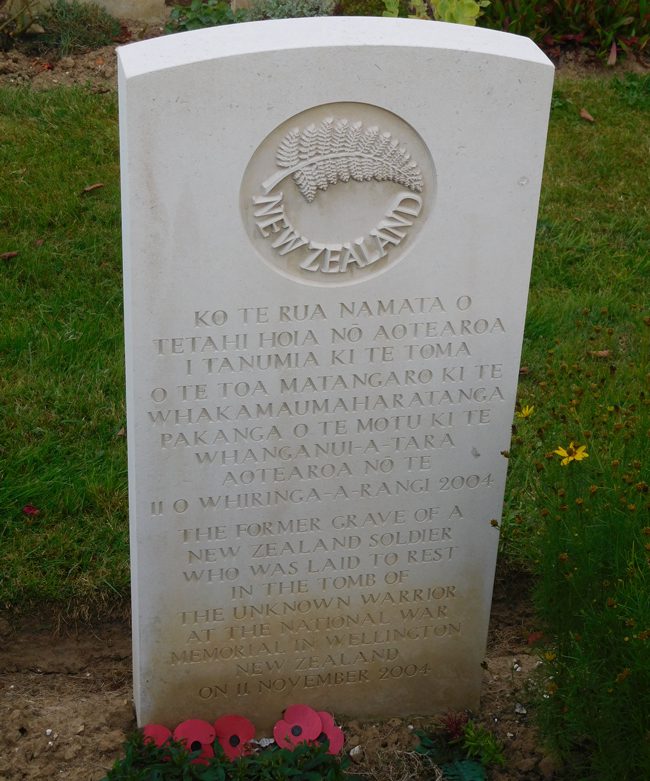

Caterpillar Valley Cemetery is a very large and peaceful area, the home of 5,569 Commonwealth burials and commemorations, a staggering 3,796 remain unidentified. The body of the Unknown Warrior that now lies in the National War Memorial in New Zealand was exhumed from here and a unique headstone remains to mark his place. The tour leaders asked if I would do the honours to lay a large poppy wreath at the monolith and I was completely caught off-guard. True to form I couldn’t stop the tears and the pit of my stomach seemed to yawn open – I felt such despair for the thousands buried around me and all I could offer was a paper poppy wreath and silent reflection.

Laying the wreath at Caterpillar Valley finally broke through my carefully curated tough outer shell. I knew coming on this trip would be difficult, just as with our visit to Auschwitz and Birkenau, and I prepared to face the realities of what we were going to experience by pushing the emotion deep down to help deal with each moment.

And then it all fell apart. A surprise extra stop was added to the itinerary when Phil, war buff and guide, found out I was Aussie. With an Australian flag flying alongside the French tricolor at the entrance, The Pozieres Windmill site was the centre of the struggle in the Somme battlefield in July and August 1916. Captured by the AIF on 4th September and as the commemorative inscription states ‘Australian troops fell more thickly on this ridge than on any other battlefield of the war.’ It saw 23,000 Australian casualities, nearly 7,000 of whom died. Charles Bean recommended the acquisition of the site to the Australian War Memorial in 1932 and his words are carved into a memorial bench at the windmill ruin which ‘marks a ridge more densely sown with Australian sacrifice than any other place on earth’. Its significance was highlighted on 11 November 1993, as the coffin containing the remains of Australia’s Unknown Soldier lay in his tomb in the Hall of Memory at the Australian War Memorial. Soil brought from the windmill site was cast over the coffin by AIF veteran Robert Comb who had fought on the Western Front. As he scattered the soil into the tomb he said – ‘Now you’re home, mate.”

The Windmill site is also officially the Pozieres Memorial Park, inaugurated on 23rd July this year. It now features 7,000 small, white crosses depicting the Australian men who died in 1916. Of the 7,000 killed, 4,112 were never identified and have no known grave – this Park is the first time in 100 years these men have ever had a cross. The crosses are laid out in the design of the rising sun on the Aussie hat badge with the long axis pointing towards Thiepval which you can see clearly in the distance. The land itself was donated by the farmer who worked it after his son brought home a charming Aussie girlfriend. It now belongs to the soldiers of the 1st, 2nd and 4th Divisions, AIF. As I was taking in the yawning expanse of white crosses, Phil pointed out ‘You’re now standing on Aussie soil,’ I couldn’t help sobbing on Julie’s shoulder. Continuing on into the small town of Pozieres, the watertower is emblazoned with a digger and AIF rising sun. It was a very proud Aussie moment and obviously remains my most stirring memory from a very crowded weekend.

The Lochnager mine crater, a remnant of the British opening their infantry assult of the Battle of the Somme on 1st July, it is immense and the stats are mind-boggling. As the official website says: The mine created a crater 91m across and 21m deep, including a lip 4.6m high. The mine itself was packed with 27,216kg of ammonal in two charges 18m apart and 16m below the surface and obliterated between 91-122m of the German dug-outs which are thought to have been full of German troops. Cecil Lewis, then an officer in the Royal Flying Corps, witnessed the explosion of the mine from his aircraft high above La Boisselle and is quoted as saying: “The whole earth heaved and flared, a tremendous and magnificent column rose up into the sky. There was an ear-splitting roar, drowning all the guns, flinging the machine sideways in the repercussing air. The earth column rose higher and higher to almost 4,000 feet.”

We walked the boardwalk around the top, reading each and every plaque attached to the boards in remembrance of a veteran, including men from my father’s old senior school – yet another reminder of the links with a distant home.

A replica of St Helen’s Tower marks the Ulster Memorial, dedicated to the 36th (Ulster) Division, made up of Northern Irish soldiers. The banners and pennants in the Memorial Room inside the tower call out support from home, patriotic rally cries and has a cool calming feel. Further up the white gravel walkway is a visitor’s centre and cafe with the best tea you’ll drink as you watch grainy archival footage while surrounded by a treasure-trove of artifacts. The site is run by volunteers Teddy and Phoebe who come out from Belfast to maintain the site and conduct information walks in the nearby Thiepval Wood. Cloaked in trees and foliage with its locked gate accessed along a dirt track down the side of a cemetery, it felt a privilege to follow along for Teddy’s clearly passionate talk at trenches and bunkers that have been uncovered and restored in original positions. It struck me afresh to be standing among the quiet wood with its gently swaying trees, so very peaceful in stark contrast to what we were hearing of its place in history. Even 100 years on, its significance to the histories of so many families in a land many miles from here remains strong and will never be forgotten. Teddy’s tireless devotion to preserving the history of the area and educating visitors is really inspiring. The researchers dig up tons of shrapnel and sometimes this is Teddy’s to redistribute. I was lucky to have a ball bearing from a bomb dropped into my hand as we walked back to the Memorial. Bit of a contrast to its former, deadly use.

It would be remiss to visit this area and not go to the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme battlefields – its iconic, staggering 45m arch with pillars clad in Portland stone bear the names of 72,194 British Empire officers and men who have no known grave. Over 90 percent of those commemorated here died in the battles of the Somme between July and November 1916. The visitors centre is excellent and educational, taking you through the time line of the battle, its chapters and locations. It was a lot to process and take in and all flew out of my mind in an instant when we walked up from the centre and around the trees to first see the arch up close. It is immense and imposing, living up to its status as the largest Commonwealth war memorial in the world. The trees press in on either side, almost trying to subdue the pain of loss felt by the families of these thousands of men whose names are carved one after the other, on and on and on they read. Again, the atmosphere was so tranquil, such peace these men wouldn’t have known when they fought here.

As we headed for the Channel and home, I felt completely wrung out, crumpled up. No school history lesson can prepare you, no documentary could capture the scale as I felt it. Driving the roads in the region, passing so many cemeteries and spotting them standing alone in farmer’s fields was a very physical lesson in the scale of just one front of the – aptly named – Great War. Even with hours of driving between the two main areas, there is no shortage of gravestones. And that’s not even all of the fallen, as Thiepval demonstrates. And it’s simply heartbreaking.

“War does not determine who is right. Only who is left.” Bertrand Russell